Are Monarch Butterflies Endangered?

This is an actively changing page. I will try to keep as much information as up to date as possible.

Monarch butterflies as a species are quite secure.

There has been a lot of confusion regarding the status of the monarch butterfly recently, stemming directly from the IUCN’s decision to classify the nominate species of monarch (Danaus plexippus ssp. plexippus) as endangered. This garnered significant media attention that was oversimplified to the point of being misleading to the general public.

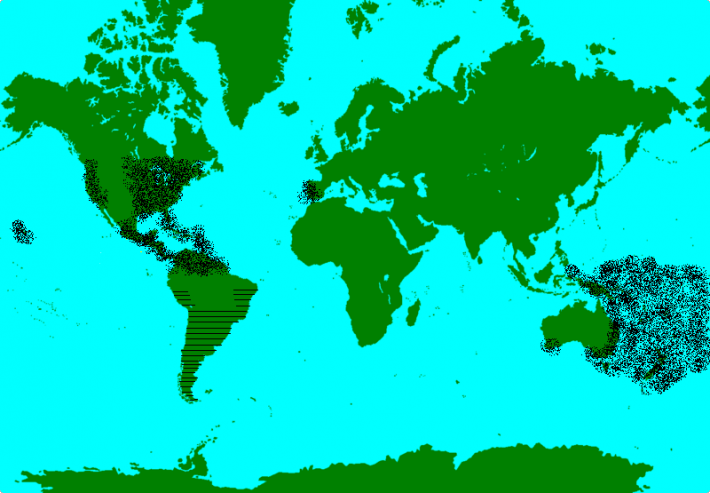

Contrary to most reporting, the monarch subspecies Danaus plexippus ssp. plexippus is actually quite secure. Most people in the United States don’t realize that the monarch butterfly can be found across the globe — not just in parts of North and South America, but also in Hawaii, the South Pacific, New Zealand, Australia, Spain, Portugal, and potentially even the mediterranean in decades to come.

The subspecies is not at risk— the migratory population of this ‘subspecies’ unique to North America is.

Map by Monarch Joint Venture — “Shaded areas on the map indicate the world-wide distribution of Danaus plexippus (the Monarch Butterfly). The stippled areas represent the range of the monarch butterfly and the striped areas represent the range of monarch sister species, Danaus erippus.”

Global Distribution

Monarch Joint Venture, a non-profit dedicated to bringing organizations together to benefit the monarch butterfly, has written a fantastic explanation regarding the global distribution of monarchs and how their migration came to be:

“Monarchs are native to North and South America, but spread throughout much of the world in the 1800's (though recent analysis supports earlier dispersal (Kronforst et al. 2014)). They were first seen in Hawaii in the 1840's, and spread throughout the South Pacific in the 1850's-60's. In the early 1870's, the first monarchs were reported in Australia and New Zealand. Monarchs also inhabit Portugal and southern Spain along the Iberian Peninsula, and the Mediterranean habitat offers a suitable environment for monarch butterflies to proliferate.

Monarchs arrived in North America from a migratory ancestor, common to both D. plexippus and D. erippus. As the last ice-age receded 20,000 years ago, the monarch population occupying the southern USA and northern Mexico began to grow and expand their range and migration annually. These expansions were stimulated by the abundance of milkweed that was growing, exploiting the novel habitat uncovered by the glacial recession. The population underwent three separate dispersions into South America, westwards to Oceania and Australia, and east across the Atlantic. Upon dispersal, the Atlantic and Pacific populations underwent a significant reduction in population size. These results, as reported in Kronforst et al. (2014), are supported by the fact that monarch populations outside of North America display high levels of linkage-disequilibrium, consistent with expectations of recent population dispersal.” — Monarch Joint Venture

What are the different monarch butterfly species and subspecies?

First, I want to say that I am not a taxonomist. My understanding of Lepidopteran subspecies is constantly growing and changing. However, it is important to understand how the monarch species classifications have evolved over time to be able to fully grasp the impact of the IUCN’s status change for ssp. plexippus.

There are three species of monarch.

The first is our very own Danaus plexippus (which also has spread across the globe).

The second is Danaus erippus, the Southern Monarch, found in tropical and sub-tropical South America.

The third is Danaus cleophile, the Jamaican Monarch, found in Jamaica and Hispaniola.

In the past, scientists thought the Southern Monarch, Danaus erippus, was a subspecies of Danaus plexippus — historically labeled as Danaus plexippus ssp. erippus. Scientists soon discovered that the two “subspecies” were incompatible, meaning the offspring produced by the mating of two different “subspecies” were unable to reproduce. By definition, this meant the two “subspecies” were in fact two completely different species entirely.

There are six subspecies and two color morphs of the monarch, Danaus plexippus.

The following information comes directly from the Wikipedia page for Monarch Butterfly:

D. p. plexippus – nominate subspecies, described by Linnaeus in 1758, is the migratory subspecies known from most of North America.

D. p. p. "form nivosus", the white monarch commonly found on Oahu, Hawaii, and rarely in other locations.

D. p. p. (as yet unnamed) – a color morph lacking some wing vein markings.

D. p. nigrippus (Richard Haensch, 1909) – South America - as forma: Danais [sic] archippus f. nigrippus. Hay-Roe et al. in 2007 identified this taxon as a subspecies

D. p. megalippe (Jacob Hübner, [1826]) – nonmigratory subspecies, and is found from Florida and Georgia southwards, throughout the Caribbean and Central America to the Amazon River.

D. p. leucogyne (Arthur G. Butler, 1884) − St. Thomas

D. p. portoricensis Austin Hobart Clark, 1941 − Puerto Rico

D. p. tobagi Austin Hobart Clark, 1941 − Tobago

Here is a link to the Butterflies of America page regarding the different subspecies of Danaus plexippus.

Having read the above I’m sure you picked up on the fact that there are supposedly two different subspecies of Danaus plexippus that may be present in the United States: the migratory and non-migratory D. plexippus ssp. plexippus and the non-migratory D. plexippus ssp. megalippe. I personally have tried to find more information on ssp. megalippe in the United States. Years ago, it was thought that megalippe MAY be present in Florida and southern Georgia, however it was later found to not be the case. Regarding the nominate subspecies D. plexippus plexippus, I found a study that collected D. plexippus from several different populations in North and South America and learned some interesting information… These were their findings:

Our new data corroborate the previously documented close genetic similarity among individuals and reveal no phylogenetic structure among populations throughout the species' New World range in North and South America. […] The evidence suggests that the monarch has colonized its current distribution in relatively recent evolutionary time. Implications for conservation and regulatory policy over interregional transfer are discussed.

What does this mean in layman’s terms? It means that the global dispersal of the monarch is so recent there is not a significant enough genetic difference to classify any population of non-migratory D. plexippus plexippus as a genetically distinct subspecies.

So what does this all mean?

There is no question that the migration of our North American population of monarchs as we know it, is at risk. We must continue to do all we can to help support their migration, including limiting pesticide use, planting fall blooming natives, establishing & protecting native milkweed, etc.

Interestingly, Danaus gilippus thersippus — a species related to the monarch found in the western United States — continues to migrate in and out of the desert despite low population numbers. This gives me hope that even if overwintering population numbers are low for Monarchs, that the migration for monarchs will not collapse.

There is also evidence, in years when the Western Population count has been low, of monarchs breeding inland rather than overwintering at the overwintering sites. This phenomenon may explain statistical anomaly that is the massive spike in overwintering monarch numbers in California the following year.

UPDATE: Monarchs at overwintering sites in California are experiencing another low count… yet there is evidence of caterpillars and butterflies breeding more inland, for example at the Googleplex.